Across the United States, 2025 marked another year of intense activity in school district bond elections. Districts large and small asked voters to approve billions in general obligation bonds — funding for construction, renovations, technology upgrades, safety improvements, and transportation. These bond initiatives, often in the hundreds of millions for metro districts and millions for smaller districts, reflect the pressing need to modernize aging infrastructure while grappling with the realities of shifting student populations.

From one recent source: in 2024, about $113.9 billion in bond initiatives went to vote nationwide.

Nationwide, 2025 is estimated to have passed $110 billion and might have exceeded 2024 but saw fails in far more rural and suburban places. Bond wins were more concentrated in urban settings and many of those districts were underenrolled, meaning they were already in a “loss” position having missed the total enrollment expected by hundreds or thousands of students. With operating budgets off by millions of dollars already, it will not be long before bonds are seen as possibly shifting capital project funds raised into operating budget to keep public schools afloat.

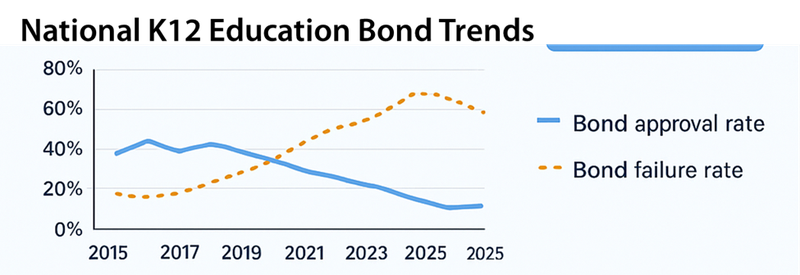

At the same time, there has been a coincident rise in school choice alternatives, including vouchers, charter expansions, and homeschooling. Families are increasingly leveraging these options to access more personalized or specialized learning environments, often outside traditional district schools. Homeschooling in particular has seen a remarkable 65% growth rate over the past decade, reflecting parental demand for individualized pacing and curricular flexibility. This trend intersects with the bond landscape: districts facing declining enrollment or competition from alternatives must now weigh the long-term cost of large-scale capital projects against shrinking or more fluid student populations. A report from one site noted that in Arizona, which has universal choice vouchers: “since 2020 … the approval rate has dropped to roughly 50%” for bonds passing from previously ~80% (for K‑12 school bonds) in the 2012‑2020 period.

The sheer scale of the 2025 bond “raise” highlights both the urgency of capital investment and the inefficiencies inherent in traditional, factory-model schooling. Many districts continue to maintain large physical footprints and staffing structures designed for enrollment levels that no longer exist. Aging buildings and deferred maintenance are driving voters to approve multi-year, multi-hundred-million-dollar bond packages, even as student populations shrink in some regions.

This context sets the stage for a broader transition: as AI-driven systems, personalized learning, and hybrid educational models expand, districts can rethink infrastructure needs and operational models. Instead of simply building larger, more expensive facilities to accommodate the same standardized schedules and classroom structures, districts could use technology to optimize space utilization, personalize student pathways, and reduce the recurring costs of underused facilities.

AI schooling doesn’t always mean a change in structure, but it can. By utilizing multiple types of AI, schools can create efficiencies in teacher time use without sacrificing live teaching.

Nationwide Snapshot

| State | District/Area | Amount Requested | Pass/Fail |

|---|---|---|---|

| Idaho | Gooding | $26.4M | Failed |

| Idaho | South Fremont | $17M | Failed |

| Idaho | Camas County | $1.75M | Failed |

| Nebraska | Wausa | $2.15M | Passed |

| Nebraska | Logan View | $21.5M | Passed |

| Nebraska | Sterling | $17.5M | Passed |

| Nebraska | Minden | $27.285M | Passed |

| Nebraska | Columbus | $43.65M | Failed |

| Nebraska | Stanton | $28M | Failed |

| Iowa | Atlantic | $22.5M | Passed |

| Iowa | Gladbrook-Reinbeck | $17.3M | Passed |

| Iowa | West Des Moines | $135M | Passed |

| Iowa | Dubuque | $70M | Failed |

| Texas | NEISD (San Antonio) | $495M | Partially |

| Texas | Port Neches-Groves | $75M | Passed |

| Texas | Midlothian ISD | $389.2M | Passed |

| Texas | Spring Branch ISD | $631.5M | Passed |

| Minnesota | Hopkins | $140M | Passed |

| Minnesota | Minnetonka | $85M | Passed |

| Minnesota | Cambridge-Isanti | $123.57M | Failed |

| Michigan | Novi | $425M | Passed |

| Michigan | South Lyon | $350M | Passed |

| Michigan | Lake Orion | $272M | Failed |

| Michigan | Gross Pointe | $120M | Passed |

| Oregon | Lake Oswego | $245M | Passed |

| Oregon | West Linn-Wilsonville | $190M | Passed |

| New York | Plainview-Old Bethpage | $114M | Failed |

| New York | Montauk | $38.41M | Failed |

| New York | Farmingdale (prop 1) | $22.5M | Passed |

| New York | Farmingdale (prop 2) | $55.85M | Failed |

| New York | Long Beach | $87.7M | Passed |

| New York | Westhampton Beach | $30M | Passed |

| New York | Bethpage Union Free | $24M | Passed |

| New York | Floral Park-Bellerose | $19.7M | Passed |

| Kansas | USD 308 | $110M | Failed |

| Arizona | TUHSD | $125M | Failed |

| Washington | Orting | $137M | Passed |

National Observations:

- The fail rate is increasing nationwide, but worse in more conservative States where the belief in public traditional schooling is waning.

- Total dollar volume is up but pass rate is down.

- Suburban/urban districts generally pass larger bonds. Large metro totals are significant, e.g., West Des Moines ($135M), Lake Oswego ($245M), Albuquerque ($350M), Spring Branch ISD ($631.5M).

- Rural/smaller districts experience more narrow votes or failures, reflecting smaller voter bases and sensitivity to property tax increases -- indicating a need for States to step in to manage any rise in inequity.

- Split propositions improve passage chances, allowing voters to approve academic/ maintenance projects while rejecting non-essential facilities.

- Supermajorities are challenging, especially in Iowa and California, often requiring multi-attempt campaigns.

Implications for the Future

- Capital allocation vs. operational flexibility: While bonds provide essential funding for physical upgrades, they do not directly address the inefficiencies of current schooling models. AI-enabled scheduling, curriculum delivery, and dynamic classroom management could help districts use existing space and staffing more efficiently.

- Risk and reward for taxpayers: Large bond approvals place long-term financial obligations on communities but also represent an opportunity to invest in schools that are increasingly adaptable to new learning modalities.

- Shift from reactive to proactive investment: Traditionally, bonds respond to visible infrastructure crises. With AI and predictive analytics, districts can anticipate facility needs, project enrollment trends, and design future-ready learning environments.

The 2025 bond bonanza, therefore, is both a snapshot of the urgent infrastructure demands of American K–12 education and a pivot point: one that underscores the need to rethink school funding, physical footprint, and operational models in an era increasingly defined by AI-driven personalization and optimization.

***