Editor’s Note: This is Part 3 in a five-part series.

In the first article in this series, we discussed the concept that the greatest matter of equity our nation’s students face is their cognitive capacity. We said we would need to be able to do three things in order to solve the problem of cognitive capacity:

- Understand each student’s cognitive strengths and weaknesses;

- Remediate, build and strengthen both weaker cognitive processes and those that are already strong; and

- Construct learning environments (technology, instruction, curriculum, etc.) incorporating science, rather than folklore.

The second article demonstrated the first part of the solution. We explained what we can do to identify students’ cognitive strengths and weaknesses as well as why it is important, particularly the evidence that cognitive skills account for more of the variance in academic performance than other factors including teacher quality and instructional time.

Once we understand each student’s cognitive strengths and weaknesses, the next task is to remediate them, to build and strengthen both weaker cognitive processes and those that are already strong.

Remediating cognitive skills is not the standard educational response that schools provide to students whose cognitive weaknesses represent stumbling blocks to academic achievement. One reason is that teachers often don’t know what those weaknesses are. The assumption is made that a student’s lack of progress or failure to acquire a skill is simply a matter of instruction. So, the material is retaught … and retaught … and retaught.

When teachers do have a clearer picture of what a students’ cognitive strengths and weaknesses are, usually because the student has been assessed and has an IEP or 504 Plan, the standard approaches include:

- Accommodations. These might include extra time on a test or assignment being given both written and oral instructions or having an aide to help take notes.

- Adjustments to the curriculum. These would include things like having fewer spelling words, reading books at a lower Lexile level or doing simpler math problems.

- Compensatory strategies. These could include more frequent scheduled breaks asking that information be repeated or using external memory aids.

Each of these approaches seeks to work around a student’s cognitive weaknesses. None of the traditional approaches offered in school actually remediate those weaknesses. But that is what we must do to address the issue of cognitive capacity and equity.

Comprehensive, integrated cognitive training does exactly that. It involves the systematic and integrated exercise and development of the processes our brains use to take in, interpret, organize, store, retrieve and apply information. With the right kind of cognitive training, cognitive skills, including executive functions, can be improved to a far greater degree than most people realize, educators included.

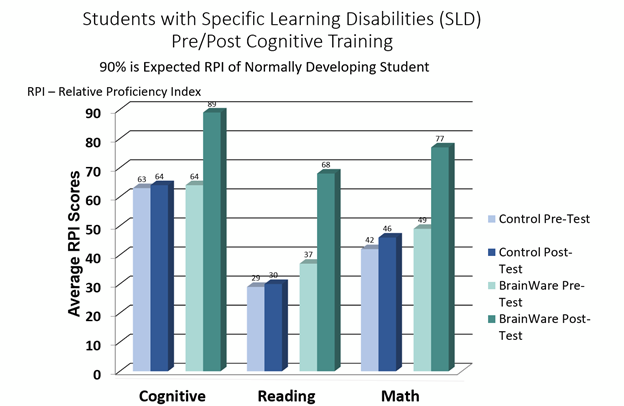

Research with students who have Specific Learning Disabilities (SLD) shows what can be accomplished with the right kind of cognitive training. Students with SLD diagnoses were randomly assigned to treatment and no-treatment groups. All the students were receiving the standard reading and math interventions the school provided because of their classification. Only the treatment group engaged in cognitive training, three to five times per week for 30 to 45 minutes each time, for 12 weeks. The students were given the Woodcock-Johnson Cognitive Battery and Tests of Achievement before and at the end of the 12 weeks. For the students in the no-treatment group, no significant cognitive change was noted, while the students who participated in cognitive training on average closed the gap cognitively almost to the level of normally developing students. The gains in cognitive capacity translated into accelerated academic gains. While the no-treatment students made the kind of incremental progress on the reading and math tests that is typical of students even when receiving common interventions, the treatment-group of students gained 0.8 Grade Equivalent in Reading and 1.0 Grade Equivalent in Math over the course of 12 weeks.

"Effect of Neuroscience-Based Cognitive Skill Training on Growth of Cognitive Deficits Associated with Learning Disabilities …” Sarah Abitbol Avtzon. Learning Disabilities: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2012

Accelerated academic gains for students with IEPs who have received cognitive training have been seen in multiple studies.

What is this like for the student and the teacher? A story from one of the studies is a great example. Rocky was a student in Mr. Sanders’s Science class (these are not their real names). Rocky struggled in Science, and although he worked, routinely got Cs and Ds on tests. Partway through the school year, Rocky was selected to participate in a cognitive training program, three times per week for 45 minutes. Mr. Sanders was aware that Rocky was in the program and so when Rocky got an A on a science test several weeks later, Mr. Sanders went down to the computer lab where the students were using the cognitive training program. He told Mr. Boehmer (his real name), who was running the program about Rocky’s test. “I know for a fact that he didn’t cheat on this test,” said Mr. Sanders. “I wanted to come down and see what this program was all about.”

Mr. Boehmer and Mr. Sanders sat down with Rocky, told him about his grade on the test and asked what was different. Rocky shrugged his shoulders, said not much and then added that he had been taking notes recently. A teacher who hears this might be inclined to say, “Well, about time! Of course, taking notes will help.” But an important insight comes from Rocky’s next comment. “I used to not be able to take notes and follow what Mr. Sanders was saying, but Mr. Sanders has slowed down and now I can.” Mr. Sanders, who had been teaching science for 25 years, knew that he hadn’t slowed down. What had happened was that Rocky’s ability to process the information at the pace of the class, to hold information in mind while writing, and to remember that information, improved. Skills like processing speed, working memory and long-term memory were now stronger.

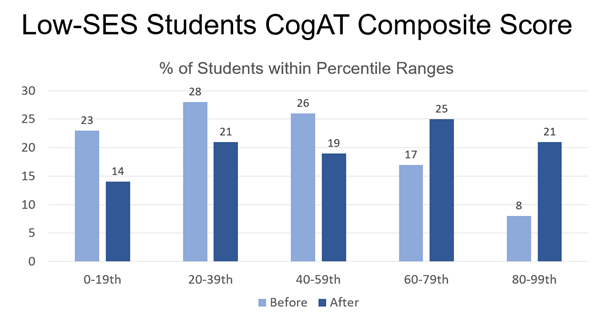

The potential to remediate cognitive skills doesn’t apply only to students with learning disabilities. Cognitive training has also shown an impact with another population where the achievement gap has been stubbornly resistant to other efforts – students from low-SES.

The chart below represents the scores of students in three high-poverty schools in South Carolina on the Cognitive Abilities Test (CogAT), the test the district uses to qualify students for its Gifted program. Students improved their CogAt scores following 12 weeks of cognitive training in a way that dramatically shifted how they would be predicted to perform academically (as shown in the chart below), including qualifying more students for the Gifted program than the district average, where none had qualified prior to the training.

Broad-Based Improvement of Cognitive Skills

It may seem strange that general training of cognitive skills could impact reading and math, because in education we tend to think about them as different sets of skills, but a student has a single brain that they bring to the learning process and to everything they do in life. Cognitive skills serve reading, math, social and emotional competence, sports performance, and every field of human endeavor.

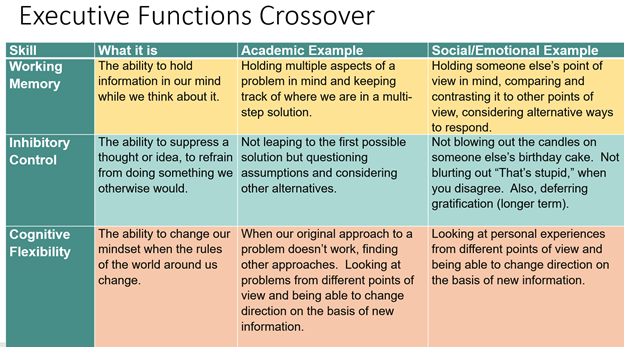

For example, most educators think of executive functions as self-regulation. And while they are involved in self-regulation, executive functions can be more clearly defined and apply to academics just as much as to social and emotional competence. The chart below gives some examples of how they apply.

In our sense of urgency to help students catch up in reading or math, we may think that the only things missing are reading, or math or whatever subject matter it is that we want them to learn. In sports, it is intuitive. Athletes train strength, flexibility, stamina and other core attributes in order to have the capacity to run for a touchdown, dunk a basket, nail a landing after a vault, swim longer, run faster ... to perform better. Students need the cognitive equivalent. Learning in school may be the only sport where participants typically get no training.

With training, each student’s capacity to learn can be increased, thereby reducing or eliminating the need to work around weaker cognitive areas and giving students full access to the learning experiences we provide them.

In the fourth article in this series, we will address those learning experiences and how they can be constructed to further address equity of access.

About the authors

Betsy Hill is President of BrainWare Learning Company, a company that builds learning capacity through the practical application of neuroscience. She is an experienced educator and has studied the connection between neuroscience and education with Dr. Patricia Wolfe (author of Brain Matters) and other experts. She is a former chair of the board of trustees at Chicago State University and teaches strategic thinking in the MBA program at Lake Forest Graduate School of Management. She holds a Master of Arts in Teaching and an MBA from Northwestern University.

Roger Stark is Co-founder and CEO of BrainWare Learning Company. For the last decade, Stark championed the effort to bring comprehensive cognitive literacy skills training and cognitive assessment within reach of everyone. It started with a very basic question: What do we know about the brain? From that initial question, he pioneered the effort to build an effective and affordable cognitive literacy skills training tool based on over 50 years of trial & error clinical collaboration. Stark also led the team that developed BrainWare SAFARI, which has become the most researched comprehensive cognitive literacy training tool delivered online in the world.