Editor’s note: This is Part two of a two-part series from renowned innovation expert John Kao. If you missed part one, you can read it here.

Worldwide, it is becoming abundantly clear that members of Generation Z — the generation born around the millennium — are more socially engaged and concerned about the condition of the world than previous generations. They are eager to learn the capabilities of innovation and entrepreneurship that will empower them to have a positive influence on the world.

The passion and idealism of this rising generation, however, is one of the most underutilized resources for good on the planet because there is a gap between what education usually provides and what young people need to know to thrive and to become socially active in the 21st century. This gap was poignantly illustrated to me by Gabe, a 12-year-old in New York, who told me point-blank, “I know I’m going to leave a legacy. I know I’m going to leave my mark. I just need someone to show me how.”

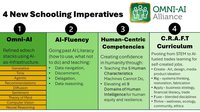

What this new era requires is the ability to generate new ideas, to develop them through mastery of such skills as storytelling, design, and collaboration and then drive these ideas to the realization of value through entrepreneurship. These are skills that employers have stated clearly as among their most important criteria for employability. And this is the new blended set of capabilities that defines the landscape of innovation.

This relates to the mission that my organization, EdgeMakers, has set for itself: to create a new learning system for innovation and entrepreneurship that will activate the idealism of young people and allow them to make a difference ahead of schedule. We believe in the importance of a new approach to innovation learning that is integrated, practice-based, and purpose-driven. Purpose provides a “why” for learning. We have suffused the learning experience with societal challenges and “wicked problems” that provide the grist for developing skills while arousing a kind of civic mindedness and appetite for activism that the world needs. And we firmly believe that these capacities of innovation and entrepreneurship are learnable and teachable— and at a young age.

We also believe that educating for innovation can be a centerpiece of an educational institution’s renewed focus on innovating education, a subject to which we now turn our attention.

So What?

Like it or not, education must transform; there is simply no alternative. It is a service industry in which its “customers” — students, parents, teachers, and funders — are increasingly dissatisfied. In my view, there is an “invalid social contract” in which students can do everything right according to the existing system and then find gaps in their employability and ability to thrive in the world.

The question that educators and educational institutions must now face is how to embark on the innovation journey. Every educational institution must prepare to navigate the Age of Innovation in the face of disruptive change. And while it is impossible to present a one-size-fits-all prescription, the following framework is intended as a starter kit to help educators and educational institutions begin that journey.

My experience shows that there are seven key ingredients that must be identified in a robust innovation agenda.

- Vision. Innovation was defined earlier as the capability to continuously realize a desired future. Vision is the description of that desired future in concrete terms that provides the vector for innovation efforts. Vision answers the question: What will the world look like if everything works out?

- Purpose. If innovation is the answer, what is the question? Why should we care about innovating, and what values and social priorities are being expressed through our innovation efforts? How will we make the world a better place?

- Process skills. Generating and developing ideas involves a suite of process skills that are teachable and learnable, and improve through practice. Adopting techniques from design to create user scenarios, future narratives, and prototypes are examples of objective processes for creativity. So are techniques for ideation, brainstorming, and visualization. Facilitation is an underappreciated skill set that should be a cornerstone of everyone’s learning experience.

- Innovation infrastructure. Innovation is the result of combining three cardinal resources — ideas, capital, and talent — in an effective manner. Eliminate or delay any leg of the tripod, and innovation efforts will be hampered.

- Narrative. Stories have a powerful ability to make ideas influential. When we hire an employee, satisfy a customer, or bring a sponsor on board, we have successfully used a story to motivate action and align effort. Stories are also critical to creating a sense of urgency, without which innovation efforts will fall short.

- Culture. This refers to the set of beliefs that guide behavior or, stated another way, that really guide behavior. One wag described culture as what people do when the boss isn’t around. Three values are key to a culture of innovation. Attitudes toward risk comprise a core cultural belief that can either enhance or impede creativity. Seeing risk as hazard will lead to conservatism. Seeing risk as learning will empower the bold. Cultures that focus on relentless business to the exclusion of needed white space for creative work will not get very far. And finally, curiosity and the desire to learn continuously are fundamental, especially in an era in which educators themselves must, in a sense, become students again.

- Leadership. In an organization built around the core value of efficiency, the leader directs effort through formal authority. In an innovation-driven organization, the leader must evangelize for the vision, support talent, provide resources, and create a sense of possibility and desire for reasonable risk taking that informs the culture of the organization.

Two other matters must be mentioned in designing an innovation agenda for educational institutions. First, one is well advised to build innovation capability with an eye toward sustaining it. In my experience, most leaders underestimate the level of investment required — of time, mind-share, and resources — to turn innovation into an ongoing way of doing business.

Second, providing the best mechanisms for innovation stewardship is key to sustaining it. This involves answering the question of who is responsible and for what elements of the process. Stewardship occurs at three levels in an organization. Buy-in at the top of the organization is essential to an innovation agenda. And having leaders who understand their role in the overall innovation agenda is key. Leaders are keepers of the vision, storytellers-in-chief, and catalysts who empower others, make useful exceptions, and provide resources.

Sustainable innovation also requires sustained bottom-up leadership — the inclusion of “all of us.” It is essential to have a robust flow of ideas and to create a culture of engagement.

What is most often missing in innovation initiatives is what I call the middleware — a coalition of the willing, in the form of an innovation task force or team — that is responsible and accountable for developing and managing the organization’s innovation strategy. This innovation action group must be central. It cannot be successful if it’s merely an exercise in form or the 11th item on a 10-item priority list.

How We Thrive

The twin agendas of innovating education and educating for innovation could not be more important, given the demands of the times, the profusion of new learning-relevant technologies, and the desire of Generation Z for a greater voice.

Education is always an answer to a question. It holds up a mirror to our society and to our values. In addition to its other responsibilities, education today must serve the goal of activating a sense of civic-mindedness in our young and equipping them to thrive in uncertainty.

John Dewey, a seminal thinker on education, stated almost a century ago that education was not only a way to gain content knowledge but also a way to learn how to live and realize one’s full potential for the greater good. I agree with Dewey and take things one step further in saying that the purpose of education must be to enable the young and their teachers to thrive in the Age of Innovation.

Each educator and educational institution will have to find its own pathway. However, I hope this framework will enable all educators and schools to begin their innovation journey in a meaningful way.

About John Kao

Dr. John Kao, founder of EdgeMakers, has spent the better part of 30 years creating compelling learning experiences for emerging innovators and entrepreneurs. His eclectic career mirrors the complexity of innovation and entrepreneurship. He was a professor at Harvard Business School, and he taught at the MIT Media Lab and Stanford’s Bowman House. He was an advisor to countries on innovation policy and is a serial entrepreneur. He also is the best-selling author of books about innovation, a Tony award-winning producer of stage and screen, Yamaha Music’s first “artist in innovation” and a Yale Medical School trained psychiatrist. Each experience has enriched his pedagogical approach. Dubbed “Mr. Creativity” and a “serial innovator” by The Economist, John Kao is a renaissance man and self-styled “innovation activist” whose creativity forms the DNA for our company.

EdgeMakers recently merged with STEM Learning Lab to focus on empowering both teachers and learners to become changemakers through STEM 2.0―the combination of high-quality STEM programs with a groundbreaking innovative thinking curriculum. The merger paves the way to provide the curriculum and professional development that empower K-12 educators to deliver the authoritative, integrated approach to teaching the disciplines of the 21st century. Learn more here.

Content in this article originally appeared in “Education in the Age of Innovation” in the Spring 2017 issue of Independent School magazine at nais.org.