TANSTAAFL

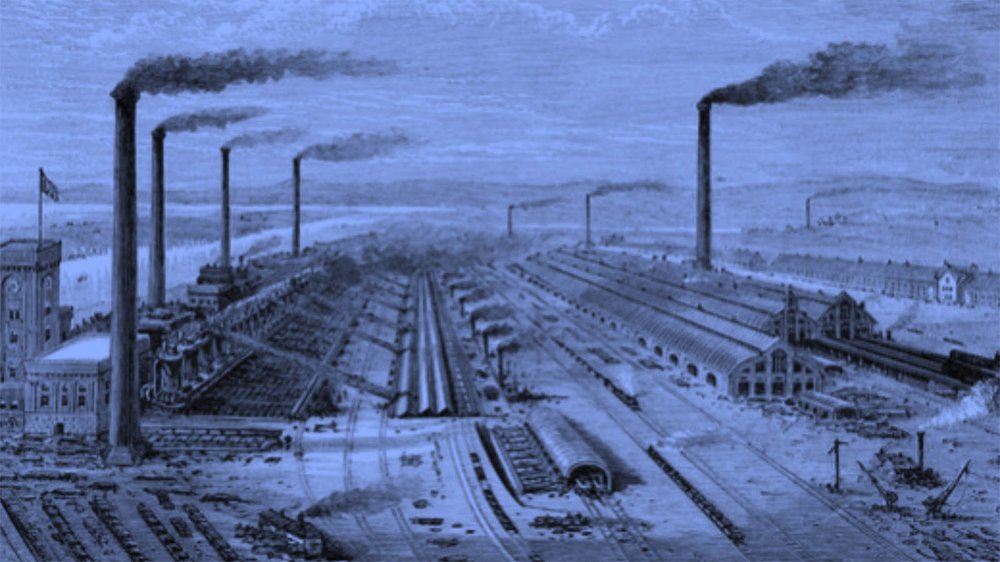

The industrial revolutions—mid 18th century, again in the early 19th century— arrived on waves of new technology. The invention of the steam engine and the sewing machine transformed work, but that’s not all—the technological bounce affected everything. For instance, concentrating population to aggregate workers in England was as transformational as introducing water wheels and spinning jennies. And if we visualize society as a body of water, the ripples of this giant industrial rock are still far-reaching. These ripples are, in addition, a mixed bag—tanstaafl (there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch). Though technology is essentially neutral, its impact is not.

Cheap goods, efficiency, uniform products, increased profit for business owners and managers came with mindless work, myriad health problems, subsistence wages and the dissolution of a holistic connection to work. And though many industrial jobs did not require much training, a whole new market for educated, skilled employees paralleled the rise of factories (especially in the second wave of industrialization in the early 20th century) and opened up education to more children than ever before. As I said, a mixed bag.

The connection between technology and education has never been more fascinating than in those days. Until now. We can have an interesting discussion about the start of the current revolution. How about 1990, when Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web? From that moment on, thinking habits started morphing. And that turmoil generates vast opportunity. Let’s focus on the opportunity side, especially for learning—and for teaching.

Technology is the answer. What is the question?

Do we spread more information or more useful information? Do we seek a world of momentary connectivity or a world built on humane connectivity? Do we encourage self-guided learning or encourage distraction? Build critical thinking skills or generate dogmatic opinions?

One of the answers of our revolution is fingertip access to all recorded human data. The salient point for me, as a teacher, is that spectacular utility. Everything else, however, is unknown. Those data come with a price. We have access to all recorded misinformation as well, and we have some compelling research about cognitive and social development deficits linked to web access. It is fascinating, and much of it is disturbing.

Technology is neutral, but its impact is not. We won’t know the lasting impact of IT for years, maybe for decades, probably not in our lifetimes. Maybe we can harness this revolution as an opportunity to change the frame of education, to finally discard the previous revolutions’ principles. Maybe we can blend IT with RT—relationship technology.

(Dis)Connections and Teachers

Connection Disconnection

1. Gargantuan amounts of data Insight and skepticism

2. Instantaneity Patience and depth

3. All 15,000 tribes* Neighbors

4. Social networks Social behavior

1. TMI: too much information. In the traditional classroom, teachers (and libraries) were the primary sources of data. One of the reasons we looked up to teachers when we were small children is because they seemed to know everything (until we became teenagers, when they knew nothing). Connection to data is a spectacular resource. If you’ve taken a self-guided tour of an historical site, you can gratify your curiosity, but you can’t ask questions and gain the benefit of a guide’s insight. In the classroom, we need the teacher’s questions to help us develop informed skepticism, so we don’t mistake knowledge for learning.

2. Socrates suggested, “Beware the barrenness of a busy life.” To mangle a metaphor, too much of our input (information, entertainment, even driving and eating) is akin to skipping a stone across a pond and thinking we understand the water. We know that the brain is malleable, not just physically, but in its programming. Without a coach/teacher/mentor to help pace understanding, there’s no place to develop connections in depth, to gain an understanding of patience and the interdependence of ideas.

3. Nearly everyone is connected through the Internet. I love having a thought-network with people all over the world—we share ideas, explore possibilities and challenge each other. Separated by thousands of miles and many time zones, we collaborate. And we are very careful to connect like neighbors, not like (a)social network transients. We can help our learners develop and value organic, complex relationships—isolation is dangerous, especially when it disguises itself as virtual connection.

4. Social behavior seems to be waning; teachers can provide the antidote to the distance imposed by (a) social media. The sky is not falling, but without some glimmerings of humility and empathy, we pay a high price in every aspect of what we do and who we become. As Margaret Wheatley suggests in Leadership and the New Science, “Power in organizations is the capacity generated by relationships.”

The Creation of a Leadership Culture

This wave of technology is neither good nor bad, but it is inevitable. Those of us passionate about and devoted to learning have the best opportunity in our lifetimes, maybe in human history, to transform how we shape and invest in what we do and what we provide.

My stepson went to a school where every aspect of leadership is shared. Everyone in the school, from the youngest leader (five) to the tallest (adults, aka the staff) is equitably charged with leadership. This means shared power and shared responsibility. The staff guides, nudges, challenges, reflects, and builds a sense of trust and vulnerability among the school community. Everyone teaches and everyone learns. All the traditional barriers that squash a leadership culture—grade levels, separate classes, bells, periods, top-down management—are AWOL: Absent without Loss.

A new kind of learning environment will quickly collapse without support at every level—students, faculty, staff, parents, et al. If we simply purchase new hardware and apps without a fundamental shift in how we understand leadership in that new environment, we may miss this opportunity. Relationship technology approaches learning from the perspective of interdependence—leadership as an equitable thread that runs through every level of curriculum, management, and continuous learning to enroll rather than to exclude.

After all, why should any of the stakeholders be invested in a process they did not help design?

If you lean toward auditory learning, try this (with a few bonus remarks):

https://www.stitcher.com/podcast/learning-chaos-1-curiosity-and-fear/e/67349212?autoplay=true

Next time: What does RT look like?

About the Author

Mac Bogert is President of AZA Learning. He began his career as an English teacher. For the past 25 years, Mac has focused on the intersection of leadership and learning. In between, He is a Musician, professional actor, yacht charter captain, staff development consultant, curriculum designer and author of Learning Chaos.

*William Ury, The Walk from No to Yes