We spend a lot of time in education talking about the promise of technology in the classroom. Terms like “personalized learning” and “AI-driven instruction” and “adaptive learning” become buzzy. We view algorithms in awe and wistfully predict their power in shaping human cognition. We look for the “next big thing” and are distracted by the promise of technology that performs like magic.

It may be prudent to ask, just what is EdTech particularly good at? Consistently, and over a long period of time? Or, right now?

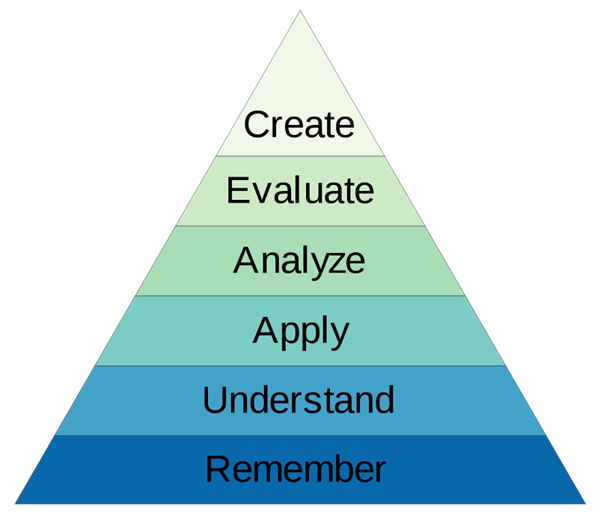

Let’s take a step back to consider how we learn. A great model for this is Bloom’s Taxonomy . At the base, the foundation of this taxonomy, are two core objectives: Knowledge and Comprehension. It is very challenging, if not impossible, to demonstrate higher levels of cognitive processes without mastering a degree of remembering and understanding.

In recent years, cognitive scientists have found several effective ways to master remembering and understanding. For example, students will likely retain more knowledge when using the retrieval practice. This is when students tap into their memory after having learned a concept and bringing forth the knowledge on a repeat basis. Transferring memories from long term memory to working memory and back again to long term memory strengthens knowledge retention.

Machines and algorithms are great tools to support the lower levels of Bloom’s taxonomy. They struggle however, for a host of different reasons, with the higher levels. In other words, the more abstract thought that is required by the students, the more the machine runs into trouble.

But that’s okay.

Because teachers and students both wrestle with the finite constraint of time – especially constructive use of time. When teachers and students offload their lower-level learning to software programs, more time can be spent tackling higher-level learning that requires humans.

For example, when I taught Social Studies, my students had to memorize many core American history facts. Sure, I could ask for essays or projects, but unless they had a basic understanding of the US Constitution, the outcome of such learning would be poor.

Flashcards work well with memorization. Flashcards with a little bit of spice (e.g., gamified) were the cherry on top for engagement. I used a (still) popular program called “Quizlet” with my students. With constant use, the software program helps students with rote memorization so they can move up the taxonomy ladder and build towards a different level of mastery.

EdTech freed me up to spend more time working with my students on higher level thinking.

Technology worked as intended when applied to an appropriate level of learning.

EdTech also allowed me to focus on a critical component of effective teaching: The building of relationships.

One final point. I don’t want to overlook the incredible value technology (in general) brings by creating efficiencies, especially when done well. Tools should make life easier or, at the very least, create optionality on what we need to focus for growth. When I first started teaching, I spent a rather significant amount of time calling parents to relay baseline information. Tools such as text messaging, email, or app notifications those tasks and freed me up to have intentional conversations with selective parents. Even today, I’d estimate a good 30 percent of what educators “do” is busy work that could be completely automated by algorithms.

Like many industries, the hype of AI is well ahead of what it can currently provide. In most cases, AI is good at replacing the lower-level functions so we can spend more time working on higher order problems.

Like being human.

About the author

Zach Vander Veen has worn many hats in education, including history teacher, technology coach, administrator, and director of technology. He loves learning, teaching, traveling and seeking adventures with his family. Currently, Zach is the co-founder and VP of Development and Customer Success at Abre.io, an education management platform.