In Part One of this series, we envisioned a world where vastly greater numbers of students could improve their cognitive skills so that they score at the 70th percentile or higher. Why the 70th percentile? Because students who perform at the 70th percentile and above generally can learn what they need to without adjustments to the curriculum and instruction. Scores on tests like the CogAT or CCAT that are predictive of academic performance are used for this purpose (among others).

Of course, for any population, only 30 percent can perform in the top 30 percent, but a subgroup of any large population may have a different distribution. Students who are selected for gifted programs must perform at least at the 95th percentile or better, for example. But what we’re talking about is taking a group of students and giving them the opportunity to improve their cognitive capacity so that they can score at the 70th percentile or higher when they weren’t previously.

As an example, all of the 2nd grade students (N=257) at three South Carolina schools took the CogAT at the beginning of the school year (the district uses the CogAT to qualify schools for a gifted program). The students then used cognitive training software for 17 weeks (2 to 3 times a week) and took the assessment again.

As shown in the chart below, only 13 percent of the students were performing at the 70th percentile or better initially (Composite Scores). After training, 35 percent of the students scored at the 70th percentile or better and the number of students performing in the lowest 30 percent decreased dramatically.

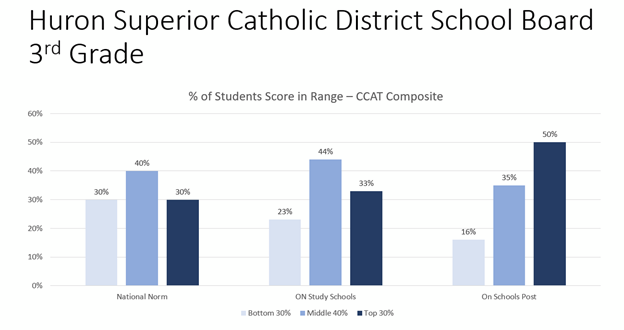

Another example comes from the Huron Superior Catholic District School Board in Sault Ste Marie, Ontario. Eight third-grade classes (169 students) in the district administered the CCAT (the Canadian equivalent of the CogAT). In this case, the students were initially performing somewhat above national norms, with only 23 percent performing below the 30th percentile and 35 percent performing at the 70th percentile or above. Following their cognitive training (3 to 5 times a week for 10 to 14 weeks), half of the students had composite scores at the 70th percentile or better.

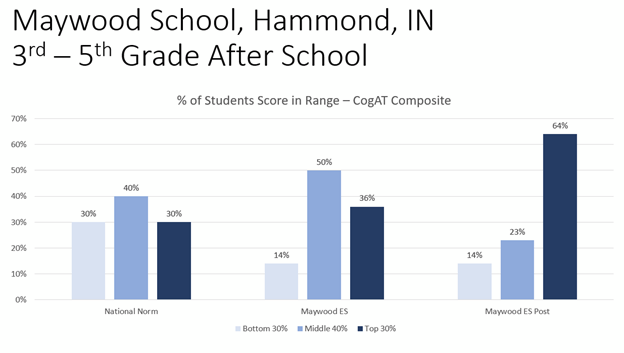

A third example comes from another school in a high poverty community, Hammond, Indiana. Students in 3rd through 5th grades were selected to participate in a cognitive training program after school, based on teacher recommendations that they could use some extra help and parent commitments to ensure they attended the program consistently. This group of students had slightly more than the expected number with CogAT composite scores at the 70th percentile or above on the pre-test. That number grew to 64 percent following cognitive training (4 times per week for 10 weeks).

The concept of getting 70 percent of students to the point where they can score on tests that predict they will be able to learn without major adjustments to the curriculum and instruction is not farfetched. It is within grasp.

Now let’s consider the implications above and beyond better student achievement.

- Students who are better focused in class (the year following the 3rd grade cognitive training program in Sault Ste Marie, the 4th grade teachers commented that they had never seen a more focused group of students ready to learn.

- Fewer behavior problems. In these examples and others, schools have experienced a significant decrease in behavioral issues.

- Fewer students who need academic interventions because they can handle the work, and interventions that work more quickly when they do.

With these students, principals and teachers can spend more time on fostering learning and encouraging personalized learning based on students’ interests.

These changes could all have financial benefits as well, but the real financial impact will come in the form of economic prosperity for individual students and their families, and for society as a whole.

Many studies have examined the economic impact of educational attainment for individuals and have calculated the increased earning power of high school graduation vs. a college degree, for example. An OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) study looked at the economic impact of low educational performance using economic models that incorporated historic patterns of country productivity (GDP). One purpose of the study was to help member countries evaluate the potential return on investments in improving educational outcomes. The strong relationship between performance on international academic measures such as the PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) and economic growth showed that small improvements in worker skills can have an unexpectedly large impact on economic well-being as reflected in GDP. The study found that raising the average score of US students to the minimum proficiency level academically would expand the economy in the United States by $72 trillion. The impact on other companies varied based on the size of their economies and how far away from minimum proficiency their average students’ scores currently are. The projected gains ranged from virtually nothing in countries like Finland and Iceland where average scores are already above the minimum proficiency level to a 15-fold GDP increase for Mexico. The increase that the OECD predicted for the US would increase GDP almost four-fold. Imagine what we could do if we were making four times the amount of money we are now – as individuals, as families, and as a country!

When we talk to superintendents and principals and teachers and students around the country, we hear the same refrain. Our school leaders can’t work any harder, our teachers can’t work any harder, and most students can’t work any harder. Trying to do more of the same is not working. What it is doing is resulting in unprecedented burnout, especially during the pandemic when the system has tried to switch and adapt on a continuous basis for so many months.

If we can’t work harder, we have to work smarter.

There is at least one other powerful implication of the evidence that cognitive skills can be developed and that students with greater cognitive capacity can more fully benefit from the learning experiences their education offers them. And that implication has to do with educational equity.

Equity of access to educational experiences is not only dependent on the external factors that schools and parents and educators provide – things like computers, textbooks, reading and math programs, programs to support social and emotional learning, well-trained and effective teachers, strong school leaders, safe classrooms, culturally appropriate and supportive education and much more. Equity of access to educational experiences is also directly related to the learning skills that students bring to them – learning skills like attention, working memory, cognitive flexibility, inhibitory control, verbal and visual memory skills, verbal and nonverbal reasoning skills, and integration of all these cognitive processes. These learning (or cognitive) skills are not equitably distributed across all student populations. The impact of poverty on cognitive development is significant and evident in many scientific studies of the brain structure and development as well as direct assessment of cognitive skills.

As the data from the three studies discussed above suggests, some schools have many fewer students than the national norm suggest with the developed cognitive capacity to learn as we expect them to learn. And as the data also suggests, that can be dramatically changed with the right kind of comprehensive integrated cognitive training. If education and economics are flip sides of the same coin, then the distribution of cognitive resources needs to play an important role in striving for equity.

About the authors

Betsy Hill is President of BrainWare Learning Company, a company that builds learning capacity through the practical application of neuroscience. She is an experienced educator and has studied the connection between neuroscience and education with Dr. Patricia Wolfe (author of Brain Matters) and other experts. She is a former chair of the board of trustees at Chicago State University and teaches strategic thinking in the MBA program at Lake Forest Graduate School of Management. She holds a Master of Arts in Teaching and an MBA from Northwestern University.

Roger Stark is Co-founder and CEO of BrainWare Learning Company. For the last decade, Stark championed the effort to bring comprehensive cognitive literacy skills training and cognitive assessment within reach of everyone. It started with a very basic question: What do we know about the brain? From that initial question, he pioneered the effort to build an effective and affordable cognitive literacy skills training tool based on over 50 years of trial & error clinical collaboration. Stark also led the team that developed BrainWare SAFARI, which has become the most researched comprehensive, integrated cognitive literacy training tool delivered online in the world. Follow BrainWare Learning on Twitter @BrainWareSafari