“There will be a shift in demand toward higher cognitive skills. Our research also finds a shift from activities that require only basic cognitive skills to those that use higher cognitive skills. Demand for higher cognitive skills, such as creativity, critical thinking, decision making, and complex information processing, will grow through 2030, by 19 percent in the United States and by 14 percent in Europe, from sizable bases today.”

–Jacques Bughin, Eric Hazan, Susan Lund, Peter Dahlström, Anna Wiesinger, and Amresh Subramaniam, McKinsey Global Institute

The AI Shift – Threat and Opportunity

With the rapid emergence of AI, a common fear is that it will replace workers and eliminate jobs. Predictions vary — estimates from McKinsey, the International Monetary Fund, the U.S. Department of Labor, and the World Economic Forum put the percentage of jobs that could be displaced by AI anywhere from 9% to 47%. But while some roles will disappear, nearly every job will be transformed. AI is now capable of performing many routine or standardized tasks — even tasks once thought exclusively human, like drafting marketing copy, creating images, or answering customer questions.

Yet this is only half the story. The World Economic Forum predicts that while millions of jobs will be displaced, twice as many new roles are likely to emerge. AI is not just replacing work — it is redefining it.

Which leads us to the urgent question at the heart of this article:

If AI can perform so much of what humans once did, what human abilities will matter most?

Some answers sound familiar — creativity, critical thinking, decision-making, problem-solving. In fact, a McKinsey Global Institute report projects a 19% increase in demand for higher-order cognitive skills in the United States by 2030. But naming those skills is not enough. That leads to the deeper, often overlooked question: Where do these skills come from — and how do we build them in every student, not just a few?

While AI reduces the need to remember information, it also dramatically increases the need to learn, adapt, and rebuild understanding when conditions change. In other words, the most valuable skill in the age of AI is not what you know. It is how effectively you can learn — your learning capacity. And that capacity is not a mindset or something we are born with and can’t change. It rests on measurable, trainable cognitive processes in the brain.

If the jobs of the future require more creativity, judgment, adaptability, and decision-making — where will those capacities come from unless we build the cognitive foundations that make them possible? This is where the conversation must shift — from AI literacy to learning capacity – from teaching students how to use AI, to ensuring they have the comprehensive integrated cognitive architecture to think with it, challenge it, and go beyond it.

Why Human Cognition Matters More, Not Less

In a world where AI can instantly retrieve more information than any human, it might seem that what we know no longer matters. But the real human advantage has never been information alone — it is the ability to make meaning, detect relevance, and rebuild understanding when conditions change. This is learning capacity — the brain’s ability to continuously adapt and construct knowledge. And paradoxically, AI makes this capacity more important, not less. Learning capacity is not a substitute for knowledge — it depends on it.

AI can generate answers, but if a student has no domain knowledge — no grasp of the concepts, vocabulary, principles, and structure of a subject, then they cannot tell if AI is accurate or absurd, they cannot ask good questions, and they cannot apply or transfer what AI provides.

Knowledge gives information meaning. Cognition makes that meaning usable. AI cannot replace either.

Cognitive Skills Fuel the Engine of Learning Capacity

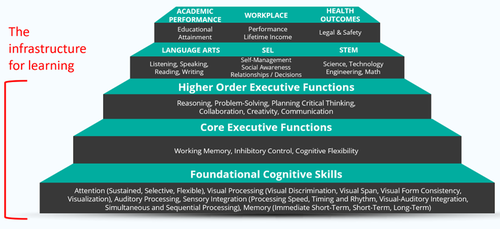

If learning capacity is what determines whether students can thrive in an age of AI, then cognitive skills are the infrastructure that makes learning capacity possible. They are not academic skills like reading or math. They are the brain’s mental tools, the underlying processes that allow us to take in information, make sense of it, store it, retrieve it, and apply it in new contexts.

The chart below shows how cognitive skills provide the infrastructure for academic performance and life success. It also shows how these skills form a system, a layered and integrated structure.

The bottom step of this chart represents foundational cognitive skills, such as attention, visual and auditory processing, processing speed, and other skills that comprise the brain’s basic cognitive operating system. They are the skills that enable us to receive, process and retain information. If any of these skills are weak, students may seem unfocused, careless, or unmotivated — but the fact is that their brains are actually working harder just trying to keep up.

The second level from the base includes the three cognitive skills that are known as Executive Functions, the mental processes that act as the brain’s air traffic control system, governing how we manage information, respond to it and adapt as circumstances change. The three core Executive Functions are:

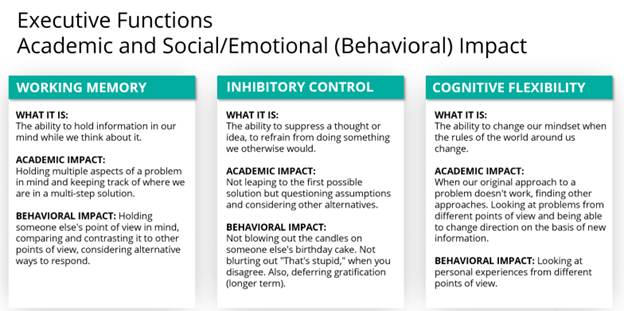

1. Working Memory

Working memory is our ability to hold information in mind while we use it. When we follow multi-step directions, do mental math, remember the beginning of a sentence by the time we reach the end, or compare what we’re reading with what we already know — working memory is doing the work. Unlike long-term memory, working memory has a very limited capacity.

2. Inhibitory ControI

Inhibitory control allows us to pause, think, and choose not to act on impulse. It helps us stop ourselves from interrupting, resist distractions, wait our turn, or stay in and study instead of going to a party. It’s the cognitive basis of self-control.

3. Cognitive Flexibility

Cognitive flexibility allows us to shift our thinking, change strategies when something isn’t working, or look at something from another perspective. It helps us transition between tasks, adjust to new rules, or rethink a problem if our first solution fails.

Many educators tend to think of Executive Functions as related primarily to behavior, but they are the same skills regardless of task. They are integral to academic skills, problem-solving, and intelligent AI use, as well as behavior, as shown in the following graphic.

Executive Functions are also the gateway to the higher cognitive processes required in an AI future. The contribution of each of the three Executive Functions is explained in the following chart.

Executive Functions & Higher-Order Cognitive Skills

| Working Memory | Inhibitory Control | Cognitive Flexibility | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planning | Keeps steps and deadlines in mind while planning and organizing them into a logical sequence | Controls impulses to skip steps or avoid planning | Modifies steps and adjusts timelines when plans change |

| Organization | Holds multiple pieces of information to know what is needed and where it goes | Inhibits impulse to shove everything in the bag or ignore mess | Adjusts approach to stay organized when systems don’t work |

| Communication | Tracks what’s been said in a conversation to respond coherently | Pauses before reacting emotionally to ensurea respectful, thoughtful response | Adjusts tone, language, or explanation depending on the audience |

| Adaptability | Stores and compares different ways of responding to a new situation | Inhibits frustration or resistance when plans change | Shifts mindset when rules or expectations change |

| Critical Thinking | Holds evidence and counterarguments in mind to weigh their validity | Resists bias or personal preference when evaluating information | Shifts between different frameworks (e.g., scientific, ethical, practical) to analyze an issue |

| Creativity | Holds different ideas simultaneously to combine them into a new concept. | Resists the impulse to go with the most obvious or conventional idea | Switches perspectives to see a problem from an unusual angle |

| Innovation | Remembers past attempts and combines lessons learned to develop new approaches | Overcoming the impulse to stick with “the way we’ve always done it” | Pivoting to apply ideas from one domain or industry to another in unexpected ways |

| Decision-making | Holds multiple options in mind while evaluating pros and cons | Suppresses impulsive choices and pauses to consider consequences | Adapts based on past experience and changing information |

Since strong Executive Functions are essential to the higher cognitive skills that AI can’t replace, it is not surprising that, according to AI education guru Mike Bentz, “Users who excel with AI aren’t just technically proficient – they demonstrate strong executive function skills that make any complex tool more effective.”

As AI rapidly transforms how we learn and work, it is increasingly clear that technology alone isn’t enough. To truly harness the power of AI, our students will need well-developed cognitive skills that allow them to prompt AI tools, to evaluate its output, and to make wise decisions. Without these core skills, especially our core executive functions of working memory, inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility, we risk over-reliance on technology, missing the human judgment, creativity, and empathy that machines can’t yet replicate. Indeed, research reported in the news on a daily basis raises concerns about the “cognitive debt” that can result from over-reliance on AI tools. In one research study, college students wrote a series of essays over four months, using either ChatGPT, a search engine or no tool other than their own brains. Among many fascinating findings in this study, the researchers observed that:

- The Brain-Only group showed strong variability in how participants approached topics, while the LLM group produced “statistically homogeneous essays, within each topic.” In other words, originality was stifled.

- EEG analysis of the students’ brains showed distinctly different patterns of neural activation “with implications for executive function, semantic processing, and attention regulation.”

- The Brain-Only groups showed activation across the strongest, widest-ranging networks. The LLM groups showed the least (up to 55% reduced magnitude of the measure).

If that is how we can expect students to fare when using AI tools, then where will all the extra creativity, critical thinking and decision-making come from? How do we keep students from losing cognitive capacity when they need more? And what has to happen for students to develop these higher cognitive skills?

Developing Cognitive Skills

Even though cognitive skills — including executive functions — are essential to learning, behavior, and adaptability in a world shaped by AI, schools do not typically teach them directly. Students are taught what to learn (curriculum) and how to demonstrate learning (tests and assignments), but the mental tools of learning itself are mostly assumed.

There are three common assumptions about cognitive skills in education:

- Students arrive with the cognitive skills they need — or they don’t.

Ability is treated as fixed rather than developable. - If cognitive skills improve, they do so automatically as students engage in academic work.

But struggling readers do not become stronger by more reading alone if their processing, memory, or attention systems are weak. - Executive functions are mostly about behavior and compliance. Many educators associate EF with organization, sitting still, or turning in homework — rather than seeing them as the core of thinking and learning.

Neuroscience tells a different story.

Cognitive skills are not fixed. They are trainable — and when strengthened, they increase a learner’s capacity to understand, remember, and apply academic content. But cognitive training is different from the type of instruction most educators are familiar with. These are skills that must be trained, not explained. We can’t lecture a student into having better working memory, faster processing speed, or stronger inhibitory control.

What does work is Comprehensive Integrated Cognitive Training (CICT™). For decades, clinicians have used cognitive training to strengthen attention, memory, reasoning, and executive functions in one-on-one therapeutic settings. What’s changed now is that technology allows these methods to be delivered digitally and at scale. CICT is:

- Integrated — targets multiple cognitive skills simultaneously (not isolated drills).

- Sequential and adaptive — challenges the learner at the edge of their ability to drive neural growth.

- Designed for transfer — improvements carry over to academics and everyday tasks.

- Sustainable — gains are measurable and long-lasting when done with sufficient frequency and intensity, in an integrated manner.

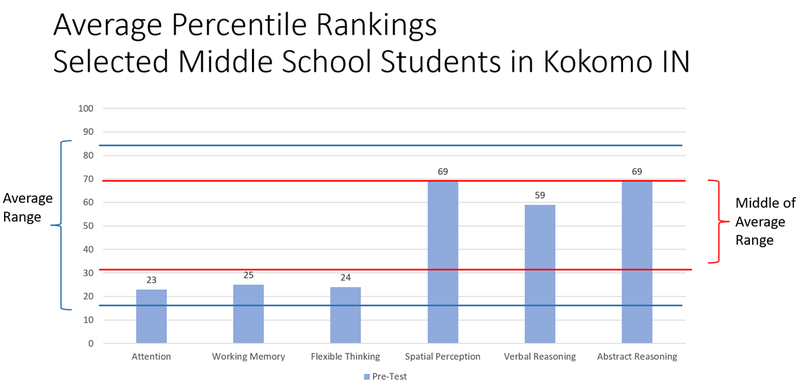

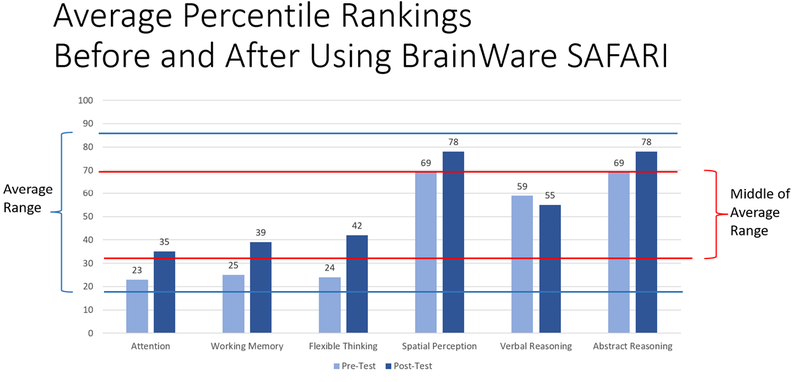

At Maple Crest Middle School in Kokomo, Indiana, students with strong reasoning skills but weak Executive Functions participated in CICT. Before training, most performed below academic proficiency not because they couldn’t understand the content, but because their brains couldn’t hold, organize, and apply information efficiently. Their average percentile rankings for Executive Functions (Attention which includes aspects of Inhibitory Control, Working Memory and Flexible Thinking) and for three complex reasoning skills, on a nationally normed cognitive assessment, are displayed in the chart below.

After an average of thirty 30-minute sessions, as shown in the following chart these students’ executive function scores rose significantly into the middle of the average range. Their nonverbal reasoning scores increased beyond their already higher-than-average levels. With full recommended implementation (36–60 sessions), we would expect even greater gains.

Maple Crest’s principal, Tom Hughes, described the situation in these words, “The reason why they’re struggling with school and learning and thinking and the reason why they have a defeatist attitude is because they just can’t. This has given them absolutely the tools to do school and so with that renewed ability and that renewed confidence we’re seeing just absolutely astronomical growth.”

If AI is changing what students need to know, it is also changing how their brains must be prepared to learn. Academic instruction alone is no longer enough. We don’t just need students who know more — we need students who can learn more. Faster. Deeper. With flexibility and resilience. And that depends on building the brain’s learning systems — its cognitive capacity — not just delivering more content.

Learning Capacity: The Ultimate Future-Proof Skill

AI accelerates information, automates routine work, and even generates ideas — but it cannot understand, make meaning, or learn from experience the way the human brain can. In earlier eras, knowledge and expertise were the primary currency of success. But now, when AI can generate information faster than we can type a question, the advantage shifts.

The most important human capability is no longer how much we know, it is how effectively we can learn. AI doesn’t replace the need to learn; it raises the bar. AI does not mark the age of the machine.

It marks the beginning of the Age of the Learner.

In a world where information is abundant, the capacity to learn continuously, critically, and creatively is the new literacy. And that capacity is not accidental — it’s built through intentional development of cognitive skills.

The AI Future: Welcome to the Age of the Learner

Creating competence in AI isn’t just about teaching students how to write prompts or use tools. Real confidence in an AI-driven world comes from something deeper: the ability to think, make judgments, and learn in ways that technology cannot. AI can retrieve information, summarize, or simulate human language — but it cannot understand meaning, weigh values, or take responsibility. That remains human work.

To guide AI, challenge it, and expand what is possible with it, students must have the cognitive capacity that comes from strong foundational cognitive skills and executive functions; the knowledge and mental models to determine whether AI-generated information is meaningful and relevant; the learning agility to adapt quickly when the technology, the problem, or the world changes.

AI can accelerate thinking — but only if the learner has the cognitive strength to steer it. Without that, AI becomes a shortcut that leads to shallow understanding, dependence, or cognitive debt.

For generations, education has focused on what students should know. That will always matter. But now, it is no longer enough because what AI can retrieve swamps that. Instead, we must also help students build:

- How the brain learns (cognitive architecture)

- How thinking is regulated (executive functions)

- How knowledge is applied flexibly in new contexts (higher-order skills)

When we develop cognitive skills intentionally through methods like Comprehensive Integrated Cognitive Training (CICT™), we don’t just help students do better in school — we prepare them to keep learning long after school ends.

AI will continue to evolve. Jobs will change. Knowledge will double faster than ever. But one thing will remain constant. Those who can learn – deeply, flexibly, and continuously — will lead. This is why AI does not signal the end of human relevance. It signals something far more powerful: the beginning of the Age of the Learner.

About the authors

Betsy Hill is President of BrainWare Learning Company, a company that builds learning capacity through the practical application of neuroscience. She is an experienced educator and has studied the connection between neuroscience and education with Dr. Patricia Wolfe (author of Brain Matters) and other experts. She is a former chair of the board of trustees at Chicago State University and teaches strategic thinking in the MBA program at Lake Forest Graduate School of Management where she received a Contribution to Learning Excellence Award. She received a Nepris Trailblazer Award for sharing her knowledge, skills and passion for the neuroscience of learning in classrooms around the country. She holds a Master of Arts in Teaching and an MBA from Northwestern University. Betsy is co-author of the book, Your Child Learns Differently, Now What?

Roger Stark is Co-founder and CEO of the BrainWare Learning Company. Over the past decade, he championed efforts to bring the science of learning and Comprehensive Integrated Cognitive Training ( CICT ™) and Cognitive Assessment, bringing it within reach of every person, and it all started with one very basic question: What do we know about the brain? From that initial question, Roger Stark pioneered the effort to build an effective and affordable cognitive literacy skills training tool, based on over 50 years of trial and error through clinical collaboration. He also led the team that developed BrainWare SAFARI, which has become the most researched comprehensive, integrated cognitive literacy training tool delivered online anywhere in the world. For more, follow BrainWare Learning on Facebook Roger is co-author of the book, Your Child Learns Differently, Now