Ever watch a good psychological thriller where your mind is blown and you can't even fathom how the events that led up to the ending could have happened?

Thinking about it afterwards, you see clues throughout the movie that make the ending obvious. At some point, you’ll come across other people who have seen the movie and they share a similar experience of shock and intrigue about the ending.

“How could we all be so dense,” you ask, “not to see the clues to the ending, where the villain was finally revealed and the master plan unearthed?”

That scenario pretty much sums up the psychological thriller that is currently playing out in schools across the land when it comes to digital devices and resources. We’ve all entered this foray into digital with hopes and dreams that it would help prepare our students for the future. In some way, we have achieved help preparing them. We have been successful creating environments where students ask more questions, design creative concepts, and dive deeper into ideas they are passionate about. However, lurking behind the scenes of this image of hope were some potential villains.

As mobile devices such as laptops, iPads, and Chromebooks made their way into schools, amazing digital access started a transition. Some questions remained after the initial thrill wore off: How would our students get to the resources they needed? How would teachers and administrators make sure that those resources were vetted by known and established entities?

This is when schools enter the scary part of the movie. Wrong choices can wreck learning results.

A Hero Comes

Teachers were and still are the initiating heroes of the whole story, but unfortunately not in charge of everything. What was found as the story continued is that, initially the textbook companies and major learning management system (LMS) providers were mildly enthusiastic about digital transition, but with several catches. This new way of teaching and learning with tons of random digital bits of knowledge, many “digitized” but not truly digital represented a tripping point for many schools. It meant systems and lots of professional development about how to use them, and maybe even multiple log-ins on top of resource site log-ins in such numbers as to already be overwhelming. More was just more confusing. It also meant teachers would be custom building digital learning for scope and sequence right when academic standards were changing nationally, a huge workload shift formerly held by publishers. The cost in teacher time to try to attain any semblance of the full-coverage subject-wise was daunting. It meant as well that teachers were no longer the sole source of knowledge and workflow because students would now log in and the distribution of the knowledge would largely be via screen learning.

Many schools making the transition to digital felt the need to hold on to the prior established modalities to maintain some normalcy by sticking with traditional methods of education before digital. This doubled down on cost as schools went digital and kept the truckloads of paper still coming.

Tech advocates have preached personalization and differentiation when it comes to devices, but much like the character choosing the wrong path in a scary movie, many schools and teachers don’t realize the trap they are walking into. Let’s take apart the clues left by the well-meaning special interests, the textbook companies and the LMS providers in our schools so we can fully understand the roles they play in this thriller called “digital learning.”

Fear-Factor

The initial transition with thousands of computing devices coming into the teaching and learning arena caused a sort of wonderment, and sometimes a little fear, of the buttons and gadgets. They were so cool…but how were we going to use them?

Not having paid publishers to build a lot of digital curriculum before, the publishing companies already in the field gave most schools a digitization of their existing textbooks. This was a sort of good-enough thing in the beginning.

Later, schools found themselves scrambling administratively to get the right students into the right classes in their systems so they could access their digital textbooks. Why? Because it is the digital roster that dictates the system “views” assigning resources to any one user. This new technical burden proved to be never-ending as students shifted and classes and teachers changed. The publishers were not programmers, so a sort of new chasm opened between the digital objects and the existing systems due to the technical structure of the files not meshing with the systems that had an immediate effect. The burden was also due to signing multiyear deals with the traditional content and systems providers, somewhat out of fear that too much change isn’t good. Instead of initially using all our devices as great personal learning tools, we locked them into just digitized content and old-system structure, essentially turning them into expensive e-readers. Sometimes they didn’t do anything at all because no content could be ported onto them because it had already been purchased without digital access (Oops.)

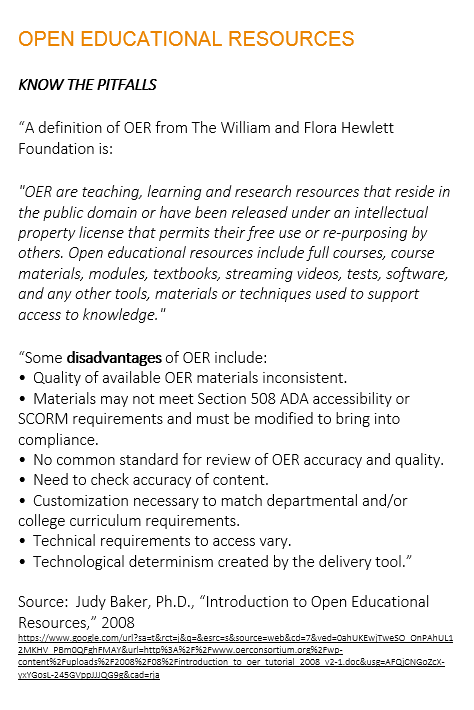

Then was born the Open Education Resources (OER) movement with a realization that the devices are not the problem, it’s was the way we were forcing our students down a traditional, rather dark (non-engaging) curriculum path, only in a “digital” format. Discovering open educational resources meant that not every vetted digital resource had to come with a price. Schools even banded together to fight against the digi tal resource apocalypse by going with OER.

tal resource apocalypse by going with OER.

Soon a major push was on by well-meaning but still sort of secretly end-revenue focused groups, and governance entities who were not really evaluating the repercussions, regarding free and especially “open” OER. The mantra went that “everything should be free,” which no one wants to argue with, but few looked at why some people would so want it to be free that they would dump millions of donated dollars into wide initiatives. It was a good but hidden reason – so that everyone could afford the digital devices by extinguishing spend on materials, of course. The reasoning went that schools couldn’t afford both the industry of professional publishers and devices, so we needed to choose apparently. Discussions about real budgets needed were therefore never had. Since devices are essentially the ground zero for going digital, and sellers of devices or other expensive software reasoned that teachers can “make their own” digital materials out of free stuff on the internet, no matter how many times the links may break mid-way through trying to deliver a lesson, the not-free part of free is that you get to do all the work as a teacher to find and build all your digital learning objects. However, you’re probably not a programmer or web designer either. Also, you don’t have endless hours to do all that customization for every single topic and subject. The hidden trickery of OER is that it is not paid so probably no one is going to mind it, upgrade it, massage it and keep developing it into a sort of great digital work of art – except you, yourself.

As a member of the audience watching this film unfold, you can’t help but empathize with the schools. Using vetted resources isn’t a bad thing, so spending millions of dollars on content provided by known publishers makes sense. However, when schools buy these “gifts” of digital resources, they rarely see the expensive “tail” that is associated with them vis-à-vis the integration costs. Also, the potential loss of student data privacy.

The path going one way and the path going the other way (paid or free) are both fraught with difficulties.

Fearson

Let me elaborate and also play out an actual scenario that I’ve personally experienced. A well-known textbook publisher comes into town promising some amazing content that is easily displayed and managed on devices. For the sake of this article let’s refer to them as “Fearson” to protect their anonymity and also tie into our scary movie theme. Fearson came in and showed some amazing examples of interactivity in a digital textbook format to a committee of teachers and administrators who quickly took the bait.

It looked amazing, and since they had just spent money on devices or gone BYOD, they figured, why not? Let’s pay some more money for snazzy interactive textbooks like these from a known publisher. Not an entirely wrong-headed move. The problem was that, behind all the magical wonder of the new digital textbooks was a harsh truth that schools rarely consider before entering into agreements with companies like Fearson.

< Enter scary music here. >

Having spent millions of dollars on these resources, the school now had to figure out how to get them on the devices and how to give the students access to them. Good user distribution, you would think, would be a natural in software. It’s digital for crying out loud. Unfortunately, this is where the happy, inspirational film went black. Rain and clouds move in, and the floorboards creaked. Screams and loud woeful echoes filled the halls. You see, the early publishing companies like Fearson were publishers at heart, not programmers. Thus, schools themselves had to determine how to integrate these resources into their systems without much support from the actual provider. Technical integrations, not just how-to-use-them-pedagogically.

< Music gets louder. The villain approaches.>

Having seen the error of the integration debacle, the teacher-heroes in the school district try to run. But as in every scary movie, they trip…over their own clunky student information system (SIS). “We just need you to change the class roster data out of your SIS, blah blah blah (incoherent technical mumbo-jumbo)” the company says while twirling their mustache and laughing maniacally. They knew that most schools don’t have the resources to actually program this kind of rostering, and they’d already received their paycheck. There was no urgency on their part to solve this problem at this point, but they could certainly sell more services to do the integration.

Our school heroes have two options at this point: either 1) hire programmers to help integrate the rosters; or 2) upload massive CSV files by hand that conform to the parameters of the textbook company. It’s enough to cause even the bravest curriculum directors to throw up their hands in despair.

How could we not see this coming? We are not programmers, dash it all!

As we stare at our empty pocketbooks, with devices full of unresponsive downloads, textbook errors, and broken apps, it's hard not feel like the victim—but again, you can’t completely blame the companies. As I stated in my recent testimony in front of the Texas Senate, districts make the choice to purchase these bulky systems partly because we choose the comfort of the known over the fear of the unknown. But it’s too late. The crimes of bad transitioning have already been committed. The bloodbath of data and expense is everywhere, and now the administrators and technology directors are left to put together the pieces of the crime to see where it all went wrong.

Enter a Solution—or Maybe Another Villain?

At this point in the movie, schools begin to scramble to solve the crime before it gets out of hand. Enter the LMS provider. For the sake of the movie, they’ll assume the character name of “BlackBard.” BlackBard offers a snazzy LTI integration and common cartridge compatibility that will easily get Fearson resources to your students.

And here’s the best part: they work on your devices! For just $8 to $12 per student more, you can even integrate other third-party textbooks into their virtual workflow solution. Ah, the unplanned for budget expense (axe murderer.)

BlackBard provides these unanticipated but now desperately needed services that do integrate digital resources -- at a cost. The problem is that they structurally perpetuate many of the traditional teacher-centered practices that districts were trying to break from when they first entered the world of mobile learning. With digital resources in place, schools have now paid millions of dollars for devices, digital textbooks, and LMS providers to “personalize” learning. But they’ve just perpetuated the traditional teaching and learning system they were trying to run from earlier in the film.

Real change has to be how one uses resources to dynamically shift the teaching and learning.

A Glimmer of Hope

After our heroes have taken a digital beating in the resources nether-region and in the systems, and are crawling through the woods looking for something—anything—to help them, there comes a glimmer of hope.

Could it be? A possible solution to fight not just the villains, but also their own helplessness that put them into this predicament in the first place?

Yes, and it’s as simple as a single truth.

True student-centered learning cannot be dictated by one LMS or textbook company. It cannot come from traditional lectures or traditional digital resources disguised as personal learning tools. It never came from one textbook, either. It comes from a mixture of new digital learning objects of all kinds magically woven into a tapestry of workability by teachers, students, and districts willing to take some risks—to step boldly and do something different than factory-model schooling that is scheduled around 19th-century agricultural calendars. Some of it will be full digital courseware. Some will be OER and mostly loose digital bits. Some will be Apps.

Companies like Learning List independently review publishers, software applications and digital content on many different levels. Knowstory.com seems promising for help in crowd-sourced vetting.

There is also a heroes’ movement amongst some schools to have teachers (and even in some cases, students) create digital courses and lessons out of these curated resources and open materials.

Third party integrators like Clever, Encore, or Classlink (running on IMS Global’s open sourced One Roster tool) can help solve the problems of student rostering and access.

Students can now sometimes learn by discovery rather than pre-digested texts via freely accessing abundant resources and solving real-world issues that weren’t often found in the pages of traditional textbooks.

Ah, now the smoke begins to clear, revealing our heroes emerging from the carnage in a slow-motion sequence that not only solves the mystery of digital integration, but gives teachers and students hope for the future.

With those problems resolved and the credits rolling, we begin to walk out of the classroom/theater feeling like we could be a superhero too.

Of course, with any good movie franchise, there is always some uncertainty whether the villain is truly gone or if they’ll come back in some other form in a sequel. In the case of digital resources, I think that next villain for curriculum and technology directors alike will be the villain’s now angry cousin: How do we analyze all these great new tools for efficacy in improving teaching and learning?

The Learning Counsel’s work in their latest Special Report is solving even that.

We have more amazing digital resources available to us than ever before. Now we just have to figure out how and when are they being used to perfect learning for our students with no scary pitfalls.