In the first article in this two-part series, we examined the reading skills identified in “the science of reading” – that is, decoding (with an emphasis on phonics and phonemic awareness), fluency, vocabulary and comprehension. We discussed the cognitive skills that enable each of those reading processes to take place in the brains of our students. We reviewed how cognitive skills can support or undermine instructional efforts based on the science of reading. We emphasized that comprehension is the ultimate purpose of reading and that, while educators measure decoding and fluency separately, the point is that they are assessing progress towards “reading” and “reading” includes comprehension.

As we connected basic cognitive processes (learning skills) to reading, we noted the difficulties that students with cognitive weaknesses are likely to have, regardless of how faithfully their reading instruction tracks the science of reading, Developing decoding skills, for example, relies on cognitive skills such as sustained attention and sequential processing. Cognitive skills also underpin fluency, vocabulary and comprehension.

Teachers can only control the teaching part of the learning equation. They do not decide what cognitive strengths and weaknesses their students have when they show up in their classrooms. Furthermore, they generally have little insight into their students’ cognitive profiles. We asked, “So, what can we do if a child has weaknesses in any of these cognitive skills? The good news is that today we know that cognitive skills can be strengthened with the right kind of comprehensive integrated cognitive training.”

In this article, we want to share some of the remarkable results that teachers and schools have seen in measures of reading achievement from the cognitive training that students have experienced.

Impact of Cognitive Skills Training on Reading Measures

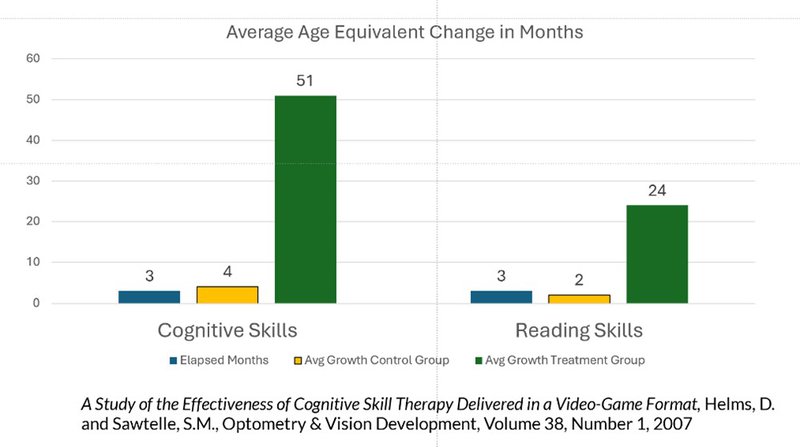

The first research that we are aware of demonstrating the connection of improved cognitive skills to stronger reading performance used the Woodcock-Johnson III Cognitive Battery and Tests of Achievement. In this study (Helms & Sawtelle[1]), students who engaged in cognitive training for 12 weeks were compared to a control group who followed their normal routine. When the students were tested the second time after 12 weeks, the control group improved their cognitive skills on average by 4 months. That is, the control group now tested as if they were 4 months older than the first time, after an elapsed time of 3 months. The treatment group, on the other hand, improved their cognitive skills by 4 years and 3 months on average, with every student experiencing significant growth. On the tests of achievement, the students in the control group improved their performance on the reading scores by 2 months while the cognitive training group improved their performance by 2 years on the reading tests.

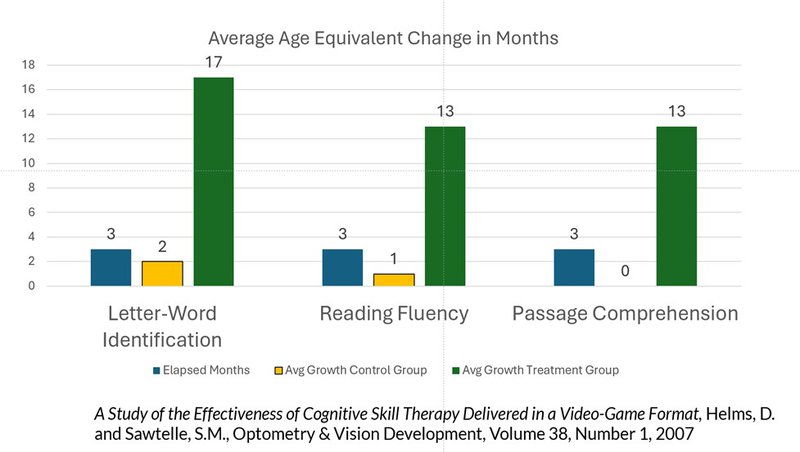

The impact of cognitive skills development affected each component of reading that was assessed, including decoding (letter-word identification), fluency (reading fluency), and reading comprehension (passage comprehension), as shown in the following chart.

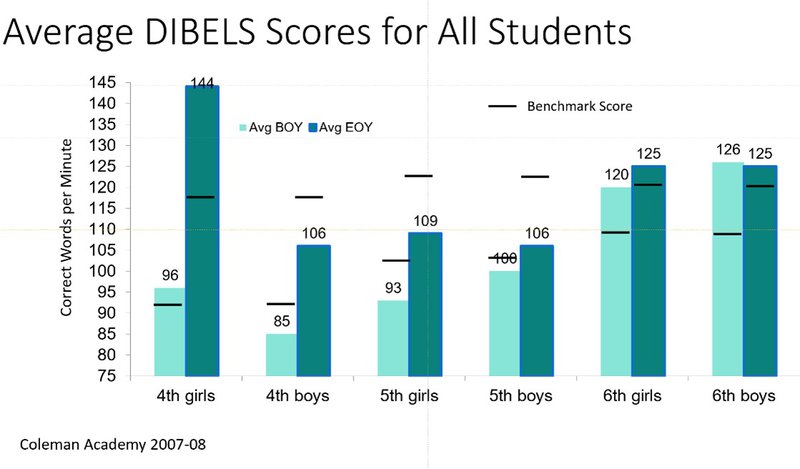

Subsequent studies have confirmed the impact of cognitive skills development on multiple aspects of the reading acquisition process. For example, one of the most common assessments of decoding and fluency is the DIBELS Oral Reading Fluency test. In an ORF assessment, students read a grade-appropriate passage for one minute. The student’s score is the number of words correct per minute (total words read minus words read incorrectly). While scores can be compared to grade-level norms, teachers also compare the growth in students’ ORF over the year to gauge their reading progress.

An Indianapolis public school decided to have its students in 4th through 6th grades engage in cognitive training to look at the impact on the students’ performance on DIBELS ORF over the year. While all six classes of students were supposed to engage in the cognitive training program, only the fourth-grade girls actually did so with fidelity, completing an average of 45 sessions. Other classes had minimal usage of the cognitive training program with no student completing more than 26 sessions and most students in the range of 0-14 sessions.

The fourth-grade girls dramatically outperformed the other classes both in terms of their gains in oral reading fluency and in the absolute level of fluency achieved at the end of the year. The chart below shows the results.

Another commonly used benchmark of the acquisition of reading skills is the NWEA MAP Reading test. Each student receives a “RIT” score (a measure of progress in the curriculum) each time they take the test; a RIT score is the level of difficulty at which the student is scoring 50% correct. Each student also receives a predicted RIT score for the end of the school year based on the initial assessment each fall.

In a Chicago public school, 3rd grade students who took part in cognitive training exceeded their predicted RIT scores by 100%, compared to the students who did not take part in the cognitive training and exceeded their predicted RIT scores by 55%.

Cognitive Training Translates to Performance on State Standardized Assessments

There certainly can be plenty of arguments about how good a job state standardized tests do of assessing reading, math and other academic subjects, but they are designed, based on the state’s standards to help determine whether students have met the expected level of performance for their grade level. And cognitive training has also been shown to improve performance on state tests.

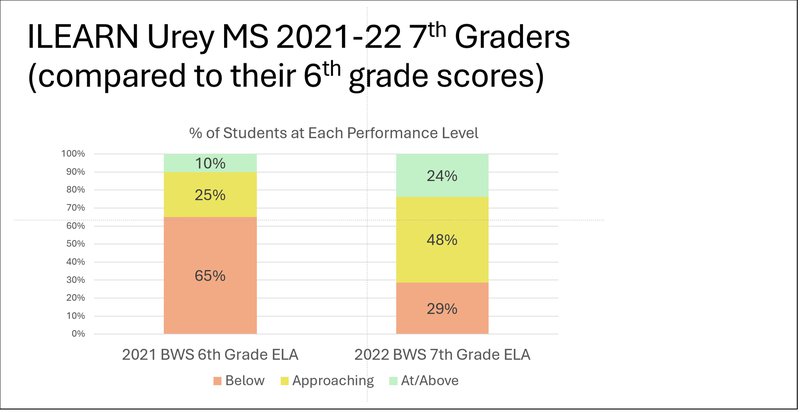

A group of 7th grade students at Urey Middle School in Walkerton, IN, were selected to participate in cognitive training because they were behind in reading and math. Other supports had limited effect on their academic progress. The chart below displays their reading scores on ILEARN (Indiana’s Learning Evaluation and Assessment Readiness Network, the summative accountability assessment for students in the state). The chart compares the performance of the students when they were 6th graders to their performance following their cognitive training as 7th graders.

Unblocking Stalled Reading Progress

As educators consider implementing cognitive training for the first time or on a broader basis in schools that have piloted it, the question often arises for whom it is best suited. Experts in the field typically hold that cognitive training can help just about every brain, but there are populations of particular concern as far as reading is concerned.

Special Ed Students

Students in the 3rd through 6th grades in the Millville Area School District (Millville, PA) completed a cognitive training program and their academic gains were assessed with the standard reading assessments used in their schools. Overall, students experienced significant gains and narrowed the gap to grade-level proficiency. Data for the students with IEPs were analyzed separately:

- The 3rd-grade students with IEPs more than doubled their WPM gains compared to the previous semester and significantly narrowed the gap to their peers without IEPs.

- The 4th-grade students with IEPs also narrowed the gap to grade level on the DIBELS ORF.

- The 5th-grade students with IEPs moved from significantly behind grade level the previous year on the GRADE assessment to ahead of grade level following their use of BrainWare SAFARI, a cognitive skills training software.

- The 6th-grade students with IEPs gained twice the expected growth on the GRADE test and narrowed the gap to grade level.

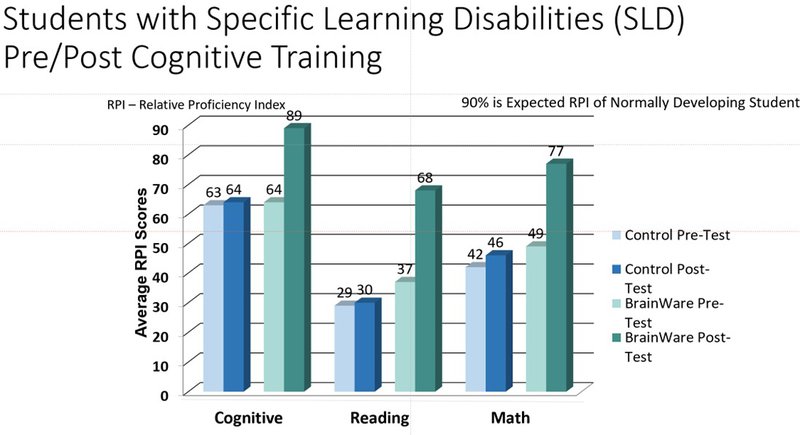

While the Millville study assessed only academic data and cannot be directly connected to cognitive impact, a peer-reviewed published study of students with Specific Learning Disabilities (SLD), evaluated both cognitive and academic gains.[2]

In this randomized, controlled study, students who engaged in cognitive training for 12 weeks on average attained a relative proficiency index (RPI) on their cognitive tests of 89%, where 90% is the RPI that would be expected of a normally developing student. Before the training, the control group and the training group both scored at 63-64% proficiency. On reading tests, the group who had engaged in cognitive training improved their reading scores by 0.8 grade equivalent in just 12 weeks.

[2] "Effect of Neuroscience-Based Cognitive Skill Training on Growth of Cognitive Deficits Associated with Learning Disabilities …” Sarah Abitbol Avtzon. Learning Disabilities: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2012

Students with Dyslexia

Researchers in Iran working with dyslexic students showed increases in memory and attention in students diagnosed with reading difficulties following cognitive training as well as a decoding test (reading words and pseudo-words).[3]

Economically Disadvantaged Students

Glenwood Academy is a private residential school in Glenwood, IL whose students come from challenging backgrounds, economically and in terms of family issues. 70% of Glenwood students are African American and 100% qualify for free and reduced lunch. The first year that Glenwood implemented a cognitive training program with students in 2nd through 8th grades, the school’s resource director administered subtests of the Woodcock-Johnson Cognitive Battery and achievement tests in reading and math. Average improvement from the pre-test to the post-test, following 10 weeks of BrainWare SAFARI use, ranged from 0.5 grade equivalents (GE) in 2nd grade to 2.9 GE in 8th grade. Average improvement on the cognitive tests ranged from 1.5 GE in 2nd grade to a high of 3.0 GE in 7th grade. The results showed a clear relationship between the improvement in underlying attention, memory and other cognitive processes and performance on academic tests.

EL Students (English Language Learners)

A cognitive training intervention was provided to 39 students in 6th through 9th grades in the All -day Program for Low English Proficiency students, School City of Hammond, Hammond, IN. Teachers noted improvement for their classes on all of the 14 behaviors in the survey, with Attention Span and Focus being the strongest area of improvement and with three of four teachers saying that their classes Improved a lot in that area. The percentage of students improving their performance over the trimester improved from the second to the third trimester, when they used BrainWare and the trend in score growth also improved. Notably, 100% of the 8th and 9th-grade students improved their reading (Scholastic Reading inventiory, SRI) scores in the third trimester, following their cognitive training experience with BrainWare. Scholastic Reading Inventory.

Cognitive Skills Are the Infrastructure for Reading Acquisition

Reading skills, as defined by the science of reading, are specific to reading. Cognitive skills, while they are not specific to reading, provide the learner with the ability to acquire reading skills. They are the mental processes our brains use to learn anything – reading, math, art history, nuclear physics, football, and chess.

At a time when national average reading scores in the U.S. continue to decline (average reading scores for students in 4th and 8th grades were lower in 2024 than in 2022), despite the use of reading instruction based on the science of reading, it is becoming apparent that instruction is only a piece of the puzzle. A student’s capacity to learn is another significant factor. We know that the reason students with specific learning disorder struggle with reading (and math) is because of weaknesses in cognitive skills. We know that economically disadvantaged students on average have less well-developed cognitive skills than their more advantaged peers. We know that individuals with dyslexia struggle with reading even with specialized instruction. And we know that we all have some cognitive skills that are weaker and some that are stronger. There is now strong evidence that cognitive training has improved reading performance to a degree that is sorely needed in today’s schools where only about a third of students are reading proficiently at grade level.

[3] Shookoohi-Yekta, M., Lotfi, Sl, Rostami, R., Mohamed-Yeganeh, N., Khodabandehlou, Y. & Habibnezhad, M. "BrainTraining by BrainWare Safari: The Transfer Effects on the Visual-Spatial Working Memory of Students with Reading Problems." AWERProcedia Information Technology & Computer Science [Online]. 2013, 04, pp1046-1052.

About the authors

Betsy Hill is President of BrainWare Learning Company, a company that builds learning capacity through the practical application of neuroscience, helping parents unlock their child’s learning potential. She is an experienced educator and has studied the connection between neuroscience and education with Dr. Patricia Wolfe (author of Brain Matters) and other experts. She is a former chair of the board of trustees at Chicago State University and teaches strategic thinking in the MBA program at Lake Forest Graduate School of Management where she received a Contribution to Learning Excellence Award. She received a Nepris Trailblazer Award for sharing her knowledge, skills and passion for the neuroscience of learning in classrooms around the country. She holds a Master of Arts in Teaching and an MBA from Northwestern University. Betsy is co-author of the new book, “Your Child Learns Differently, Now What?”

Roger Stark is Co-founder and CEO of the BrainWare Learning Company. Over the past decade, he championed efforts to bring the science of learning, comprehensive cognitive literacy skills training and cognitive assessment, within reach of every person, and it all started with one very basic question: What do we know about the brain? From that initial question, Roger Stark pioneered the effort to build an effective and affordable cognitive literacy skills training tool, based on over 50 years of trial and error through clinical collaboration. He also led the team that developed BrainWare SAFARI, which has become the most researched comprehensive, integrated cognitive literacy training tool delivered online anywhere in the world. For more, follow BrainWare Learning on Twitter @BrainWareSafari. Roger is co-author of the new book, “Your Child Learns Differently, Now What?”